History of Blue-Green Deployment

In 2005, two developers named Daniel North and Jez Humble were tackling problems with their e-commerce website. Even with a good testing system in place, errors were still being detected in production, much later than they desired.

A detailed root cause analysis showed that there was a significant difference between testing and production environment, and this difference resulted in frequent failures.

What they did next was very unconventional for their time. Rather than overwriting over the older version of the application, they made the new version run parallel to production.

As they did not have load balancers to divert traffic to the new version they had to improvise. With the help of a new domain, North and Humble smoke tested the new version on the production environment. Once they were satisfied with the results of the tests they would just point the Apache Web Server to the new application folder. In case users later found issues with the new version they would run a single command and point the Apache Web Server back to the older application. This would act like an instant rollback and restore user services immediately.

This strategy greatly improved error detection because test and production applications were now running in similar environments. After achieving great success with this strategy, they coined the term Blue-Green deployment strategy to give it a name.

How the Blue Green Deployment Strategy Works?

Before an organization plans to use a Blue-Green deployment strategy for its application releases, they need to be certain that

-

- Two identical environments are available.

- The development team needs to be certain that their new code can run alongside the old code because both of them will be running at the same time in production, side by side.

- There is also a need for a router or a load balancer so that users can be switched from one version to the other.

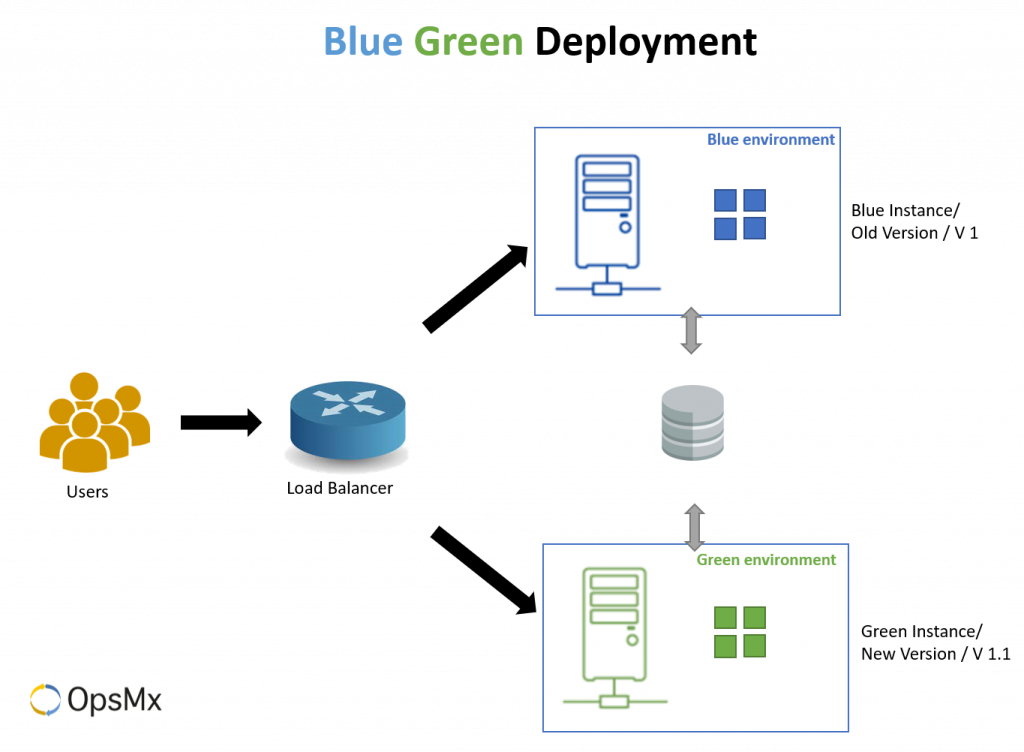

As shown in the image, let us assume that version 1 is the current version of the application and we want to move to the new update, version 1.1. Version 1 will be called a blue environment and version 1.1 will be called the green environment. (Some blogs across the internet may define the currently running version as a green instance, but that is hardly a problem as it is just a naming convention. Similarly, some people use “Red Black” – the concepts are identical.)

The Blue-Green deployment process can be broken down into 4 phases

1. Setting up a load balancer to route users

Now that we have two instances named Blue and Green, we want users to be able to access the new green (v 1.1) instance rather than the older Blue instance. For this to happen, we normally use a load balancer instead of a DNS record exchange because DNS propagation is not instantaneous.

This is where load balancers and routers help in switching users from the Blue instance to the Green one. There is no need to change DNS records as the load balancer will still reference the same DNS record but routes new traffic to the Green environment. This allows us to be in full control of the users. Full control is desired because it will be necessary to quickly switch them back to version 1 (the blue instance) in case of a failure in a green instance.

2. Executing the update

Once our green instance (v1.1) is ready we move that into production and run it parallelly with the older version. With the help of their load balancer, traffic is switched from blue to green. Most users won’t even notice that they are now accessing a newer version of the service or application.

3. Monitoring the environments

Once the traffic is switched from the blue to green instance, the DevOps engineers get a small duration of time to run smoke tests on the green instance. This is crucial as they need to figure out if there is an issue with the new version before users are impacted on a wide scale. This ensures that all aspects of the new versions are running as they should be.

4. Deployment or rollback

During the smoke tests, if any bugs are detected or there is a performance issue, the users can be quickly diverted back to the stable Blue version without any substantial interruptions.

After an initial smoke test, the new version is monitored closely, as some errors may be discovered only after the new (green) version has been live for some time. During all this time the older blue version is always on standby. After an appropriate monitoring period, the green instance becomes the blue instance for the next release.

Benefits of Using Blue-Green Deployment Strategy

- Seamless customer experience: users don’t experience any downtime.

- Instant rollbacks: we can undo the change without adverse effects.

- No upgrade-time schedules for developers: no need to wait for maintenance windows

- Testing parity: the newer versions can be accurately tested in real-world scenarios

The Blue-Green strategy is a perfect practice for simulating and running disaster recovery practices. This is because of the inherent equivalence of the Blue and Green instances and a quick recovery mechanism in case of an issue with the new release.

As we have seen in the case of Canary deployment, the testing environment may not be identical to the final production environment. In canary, we use a small portion of the production environment and move a small amount of traffic to the new system. But to simulate an actual production scenario a similar baseline instance is created that then is compared with the canary release. Read more about Canary Analysis here.

Gone are the days when DevOps engineers had to wait for low traffic windows to deploy the updates. This eliminates the need for maintaining downtime schedules and developers can quickly move their updates into production through the Blue-Green strategy, as soon as they are ready with their code.

Challenges of Adopting a Blue Green Deployment Strategy

- User routing: Failed or stuck user transactions/sessions when reverted instantly

- Costs: High infrastructure costs

- Code compatibility: running two versions of the applications in parallel.

1. Errors when changing user routing

Blue Green is the best choice of deployment strategy in many cases, but it comes with some challenges. One issue is that during the initial switch to the new (green) environment, some sessions may fail, or users may be forced to log back into the application. Similarly, when rolling back to the blue environment in case of an error, users logged in to the green instance may face service issues.

With more advanced load balancers these issues can be overcome by slowing moving new traffic from one instance to another. The load balancer can either be programmed to wait for a fixed duration before users are inactive or force close sessions for the users still connected to the blue instance post the specified time limit. This might slow down the deployment process and may result in some failed and stuck transactions for a very small fraction of the users. But this will provide an overall seamless and uninterrupted service quality as compared to the method where routers force the exit of all users and divert traffic.

Seamless Blue Green Deployment

Instantaneous Blue-Green Deployment

2. High infrastructure costs

The elephant in the room with Blue-Green deployments is the infrastructure costs. Organizations that have adopted a Blue-Green strategy need to maintain an infrastructure that doubles the size required by their application. If you utilize elastic infrastructure, the cost can be absorbed more easily. Similarly, Blue-Green deployments can be a good choice for applications that are less hardware intensive.

3. Code compatibility

Lastly, the Blue and Green instances live in the production environment so developers need to ensure that each new update is compatible with the previous environment. For example, if a software update requires changes to a database (adding a new field or column for example,) the Blue Green strategy is difficult to implement because at times traffic is switched back and forth between the blue and green instance. It should be a mandate to use a database that is compatible across all software updates (as some NoSQL databases are).

Common Practices

1. Choose load balancing over DNS switching

Do not use multiple domains to switch between servers. This was a very old way of diverting traffic. DNS propagation takes from hours to days. It can take browsers a long time to get the new IP address. Some of your users may still be served by the old environment.

Instead, use load balancing. Load balancers enable you to set your new servers immediately without depending on the DNS. This way, you can ensure that all traffic is served to the new production environment.

2. Keeping databases in sync

One of the biggest challenges of blue-green deployments is keeping databases in sync. Depending on your design, you may be able to feed transactions to both instances to keep the blue instance as a backup when the green is live. Or you may be able to put the application in read-only mode before cut-over, run it for a while in read-only mode, and then switch it to read-write mode. That may be enough to flush out many outstanding issues.

Backward compatibility is of utmost importance when business is very critical. Any new users or data on the new version must have access in the event of a rollback. Otherwise, the business might stand a chance to lose out on new customers

3. Execute a rolling update

The container architecture has enabled the use of a rolling or a seamless blue-green update. Containers enable DevOps engineers to perform a Blue-green update only on the required pod. This decentralized architecture ensures that other parts of the application do not get affected.

Conclusion

We want to conclude that the Blue-Green Strategy, although involves cost, is one of the most widely used deployment strategies. Blue-green deployment is great particularly when environments are consistent between releases, and user sessions are reliable even across new releases.